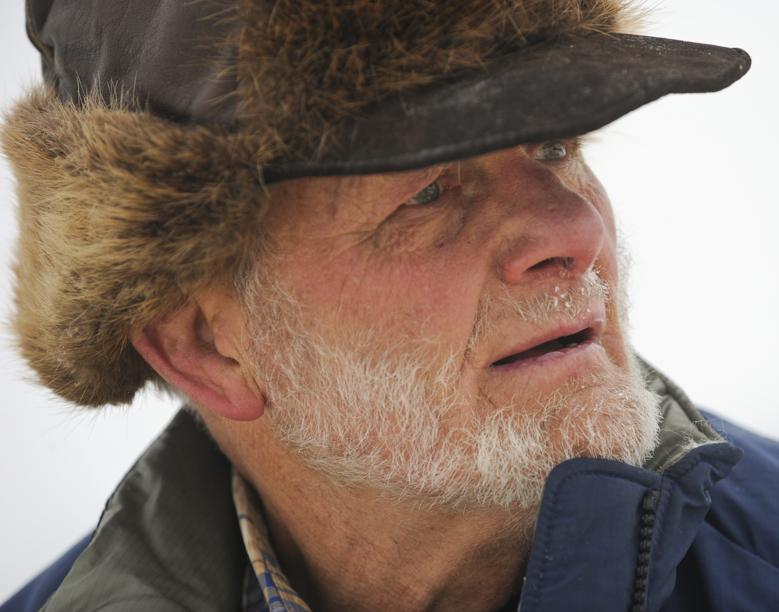

Dan Seavey, who as a history teacher in Alaska became fascinated by the Gold Rush-era Iditarod Trail and helped stage the first dogsled race along the 1,000-mile route in 1973 to begin an annual winter rite and a supreme test of wilderness endurance, died May 8 at his home in Seward, Alaska. He was 87.

Mr. Seavey died while tending to his sled dogs, said his grandson Danny Seavey, but no cause was given.

In Alaska, the Iditarod occupies overlapping identities as a celebration of frontier history and an unparalleled challenge across the interior to reach Nome on the Bering Sea. For more than five decades, Mr. Seavey was one of the guardians of the race and patriarch of a family of mushers who include two multiple winners, his son and grandson.

The idea for the Iditarod race began with a handful of adventurous souls and a mostly forgotten trail, which was used in the early 20th century by gold prospectors and settlers. The use of dogsled teams was later eclipsed by planes and snowmobiles.

Then in the 1960s, some dogsled events were held along segments of the trail. As Mr. Seavey and others planned a competition along the complete route, more than a few critics wondered if the risks were just too high. “They questioned in front of me the wisdom of even going on that first race,’’ he told KTUU television in Anchorage. Another of the race organizers, Joe Redington Sr., took out a second mortgage on his house to help fund the event.

In early March 1973, 34 dogsledders – including Mr. Seavey – set out from Anchorage. Alaskan newspapers gave front-page coverage as the mushers passed near towns and as word came that others had dropped out.

Mr. Seavey carried a tape recorder to capture his thoughts and accounts, which were saved and later used in his book “The First Great Race’’ (2013). When not using the recorder, Mr. Seavey stashed the batteries in his parka to keep them from freezing. His 12-dog team included a lead dog, Genghis, and others with names such as Koyuk, Snippy, and Crazy.

“Those wonders of God’s creation,’’ he wrote, “who weathered Arctic gales, slept in snowbanks, suffered exhaustion, sore, raw feet and, to some degree, human ignorance and neglect.’’

He also had aboard his sled 350 souvenir letters sold for $1 each with plans to mail them from Nome. “If I make it,’’ he added. He and 21 other teams did. Mr. Seavey finished third in 20 days, 14 hours and 35 minutes – about a half-day behind the winner. (Current winners finish in less than 10 days.) The finish line was improvised by pouring Kool-Aid in the snow.

“We were wandering around in the wilderness, lost, for some of the time out there,’’ he said in a 2022 interview with the Anchorage Daily News. “Whatever it took to get to Nome.’’

Mr. Seavey took part in the race four more times, the last in 2012 at age 74. He finished 50th in 13 days, 19 hours and 10 minutes. His grandson Dallas Seavey won that race in 9 days, 4 hours, and 29 minutes in the first of his six victories. Mr. Seavey’s son Mitch has won the Iditarod three times.

Once asked to describe his most harrowing moment on the Iditarod, Mr. Seavey recounted crossing a river in the 1974 race outside of the abandoned roadhouse site at Rohn, three days into the trek. The ice began to buckle. “I was wondering to myself if we were going to go all the way through,’’ he was quoted as saying on the Iditarod website.

The numbing-cold water was at his knees. “The dogs were sinking pretty deep, too,’’ he said. “Some of my smaller dogs might have been doing the doggy paddle at that point.’’ They managed to reach the other side, only to find a group of bison on the banks.

“As we started running again, the buffalo ran with us,’’ he recalled. “They ran in front for a good mile and a half, and we just followed right behind. Then they just disappeared, and we kept going for a bit until I found a good place to set up camp and build a fire.’’

For Mr. Seavey, the Iditarod was never fully about the race, he often said. He saw it more as an immersion into Alaska’s past, which he began to explore in the 1960s as a history teacher newly arrived from Minnesota. The lore and significance of the trail, in Mr. Seavey’s view, was being slowly lost at the time.

The memories included a 1925 dog team run of serum to Nome along part of the trail during a diphtheria outbreak. A statue of a lead dog in that medical mission, Balto, was erected in Manhattan’s Central Park.

“Even the word ‘Iditarod’ was lost,’’ Mr. Seavey told the St. Cloud Times in 2014. “A lot of people, I guess me, too, didn’t even know how to pronounce the word. There was a reeducation process that had to go on.’’

The inaugural Iditarod, Mr. Seavey said, was an attempt to rebuild a tangible connection with the trail, which takes its name from a central Alaskan outpost (now abandoned) that was the site of the last major Alaskan gold rush in 1909. He playfully dubbed the first race “a great camping trip.’’

Five years later, the Iditarod Trail was designated a National Historic Trail. (The race now uses alternating starting points depending on the year.)

“You might be interested in history of the game of tennis, but can you really know what tennis is all about unless you at least try to play it?’’ Mr. Seavey once said. “To me, physical experience is most important in learning about something.’’

“You can talk about a segment of the trail being used,’’ he added, “but unless you run a team down the Yukon from Ruby to Kaltag, it’s just an academic exercise.’’

Daniel Blake Seavey was born in Deerwood, Minn., on Aug. 19, 1937. His father worked in iron mines, and both of his parents helped run the family farm.

As a child, Mr. Seavey imagined Far North adventures while listening to the radio drama “The Challenge of the Yukon,’’ later known as “Sergeant Preston of the Yukon,’’ about battling wrongdoers during the Gold Rush. In 1961, he received a teaching degree from St. Cloud State College (now St. Cloud State University) and two years later headed for Alaska with his wife, the former Shirley Anderson. They met years earlier when Mr. Seavey was 19 and working a summer job as a carnival wrestler.

In Seward, Mr. Seavey was hired to teach high school history. The family later built a homestead – originally with no electricity or indoor plumbing – following a devastating 1964 earthquake and tsunami that hit southern Alaska and claimed more than 130 lives from Canada to Hawaii.

At the family cabin, Mr. Seavey began to acquire and train sled dogs. Mr. Seavey later served on the board of groups including the Iditarod Trail Committee and the Iditarod Historic Trail Alliance. He retired from teaching in 1984. “I admit to being a hardcore Iditarod junkie,’’ he said.

As climate change brings warmer winters to Alaska, the Iditarod has been forced to adapt by shifting the starting line farther inland from coastal Anchorage and diverting the route from thinning sea ice near Nome.

His wife of 59 years, Shirley Seavey, died in 2017. He leaves three children; 10 grandchildren; 20 great-grandchildren; and a brother.