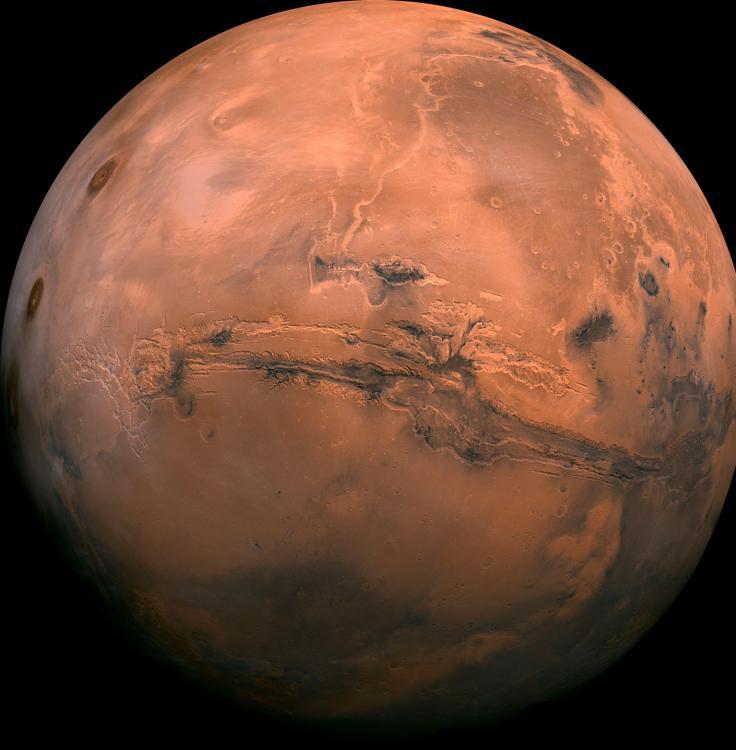

PROVIDENCE – Why exactly is the “red planet’’ red?

Researchers at Brown University and the University of Bern have a theory on why Earth’s neighbor has its signature color, and it suggests Mars may have once had a wetter environment, and therefore, a necessary ingredient for supporting life.

Published recently in the journal Nature Communications, the results of their study indicate Mars’s reddish complexion may in large part be due to the iron mineral ferrihydrite, which needs water in order to form.

While the prevailing theory is that “a dry, rust-like mineral called hematite’’ gives the planet its hue, researchers say their analysis of data from Martian orbiters, rovers, and laboratory simulations suggest that may not be the case.

“The fundamental question of why Mars is red has been thought of for hundreds if not thousands of years,’’ Adomas Valantinas, a postdoctoral fellow at Brown who started the research as a PhD student at the University of Bern, said in a statement.

“From our analysis, we believe ferrihydrite is everywhere in the dust and also probably in the rock formations,’’ Valantinas said. “We’re not the first to consider ferrihydrite as the reason for why Mars is red, but it has never been proven the way we proved it now using observational data and novel laboratory methods to essentially make a Martian dust in the lab.’’

To conduct the study, researchers dug into data from previous Mars missions, “combining orbital observations from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the European Space Agency’s Mars Express and Trace Gas Orbiter with ground-level measurements from rovers like Curiosity, Pathfinder and Opportunity,’’ according to Brown.

“Instruments on the orbiters and rovers provided detailed spectral data of the planet’s dusty surface,’’ university officials said. “These findings were then compared to laboratory experiments, where the team tested how light interacts with ferrihydrite particles and other minerals under simulated Martian conditions.’’

Hematite usually forms under drier and warmer conditions than ferrihydrite, which is created in “water-rich environments’’ where cool water is present, suggesting Mars, billions of years ago, may have once been capable of sustaining liquid water, which is necessary for life, Brown said in a press release.

“What we want to understand is the ancient Martian climate and the chemical processes on Mars — not only ancient, but also present,’’ Valantinas said in a statement. “Then there’s the habitability question: Was there ever life? To understand that, you need to understand the conditions that were present during the time of this mineral formation.

“What we know from this study is the evidence points to ferrihydrite forming, and for that to happen there must have been conditions where oxygen, from air or other sources, and water could react with iron,’’ Valantinas added. “Those conditions were very different from today’s dry, cold environment. As Martian winds spread this dust everywhere, it created the planet’s iconic red appearance.’’

Researchers will have to wait until samples from Mars are brought back to Earth to confirm their study. NASA said last year samples from the ongoing mission to the Martian surface will not arrive until 2040.

In the meantime, the study’s senior author, Jack Mustard, a planetary scientist at Brown, called the research a “door-opening opportunity.’’

“It gives us a better chance to apply principles of mineral formation and conditions to tap back in time,’’ Mustard said in a statement. “What’s even more important though is the return of the samples from Mars that are being collected right now by the Perseverance rover. When we get those back, we can actually check and see if this is right.’’

Christopher Gavin can be reached at christopher.gavin @globe.com.