Princess Diana was a global celebrity from the time millions watched her wedding to England’s Prince Charles in 1981 through the very public disintegration of their marriage, her sudden death in 1997, and the outpouring of grief that followed. But that was three decades ago, and there have been plenty of royal uproars since, most notably the brouhaha over her son Harry marrying a mixed-race American actress. Does Diana still matter in the 21st century?

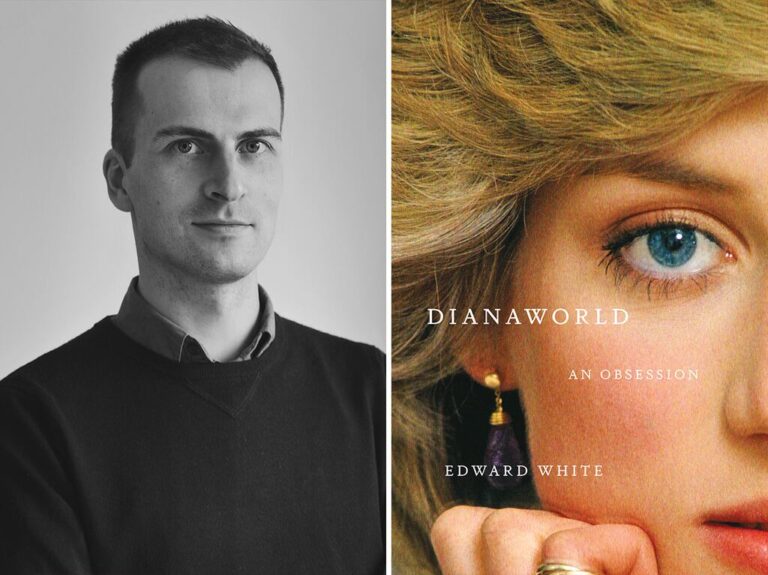

Absolutely, says Edward White, who sees her as “a woman of mythological complexity and far-reaching significance.” If anyone can justify that claim, it should be White, whose two previous books revealed a cultural critic of exceptional acuity and range. “The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America” reclaimed from obscurity a key figure in 20th-century culture, one of the earliest voices to champion the popular arts as equal in power and importance to the fine arts. “The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock: An Anatomy of the Master of Suspense” was equally astute in its examination of how a deeply insecure man harnessed his anxieties to create supremely assured films.

“Dianaworld” blends a consideration of the subject’s personality with an assessment of their impact, but it’s more scattershot than White’s two previous books. Dealing with a woman who, despite some laudable humanitarian work, was mostly famous for marrying a prince, being openly unhappy in the royal family, and dying in a car chase with paparazzi, White grasps for a new approach to very familiar material. His is “less a biography of Diana, more the story of a cultural obsession,” he declares. “Each chapter of the book addresses Diana’s connection with different communities, groups, and individuals who have, in some way or other, shaped her singular reputation.”

‘Twelve Lives,’ one master of suspense

Well, sort of. The first chapter, “Blood Family,” is indeed about the Spencers, reminding us that “the people’s princess” came from the highest echelons of the English aristocracy, and the second is about Diana’s complicated relations with “The Rat Pack,” as she dubbed the journalists on the royal beat. From there, the communities and the coherence get fuzzier. A chapter titled “Will the Real Diana Please Sit Down” wanders from the “not overwhelmingly favorable” reactions to her wedding dress through press coverage of her clothing and appearance to a peculiar digression about Diana look-alikes and then to a discussion of painted portraits that don’t look like her, all leading to the tenuous conclusion that “her capacious dress-up box has created confusion about who she really was … it has been difficult to tell where Diana stops and the rest of us begin.” Next, “Don’t Do It Di!” posits an interesting, if debatable point: “Diana, the everywoman, Diana, the superwoman. These were the poles between which much of her reputation was framed … illuminating of contemporary conversations about gender and the lives of women in a way that is still bitingly relevant.” Instead of pursuing this argument, however, White moves on to comparing the image of Diana as an ideal woman with royal predecessors such as the Queen Mother, and to the “mythology” that linked her to Marilyn Monroe and Jackie O as someone “soft, vulnerable, and sad” — to what end isn’t clear.

White’s razor-sharp prose is as pleasurable as ever, nailing “that unmistakable mixture of lasciviousness and archaic deference that the tabloids favored when writing about Diana,” or describing the photos of her being mobbed in Australia as “a scene that lands somewhere between Christ among the multitudes and Beatlemania.” In “Dianaworld,” regrettably, such shrewd comments generally appear in asides. Most of his insights feel old, as when he tells us that Diana’s feelings of neglect and rejection, sparked by the loss of her mother in an ugly divorce and deepened by her chilly relations with the royal family, were “central to the story she told us about herself, and the place she occupies in the collective imagination.” White goes on to link this image of her as someone who could relate to the despised and outcast as a (very privileged) fellow victim with the well-worn topics of her charitable work for people with AIDS and other marginalized groups and with many women’s perception of Diana as an emblem of the wronged wife. Only his discussion of the sense of connection with Diana expressed by immigrant women of color, who felt as unwelcome in Britain as she did in the royal family, offers something unexpected.

‘The Tastemaker’ on Carl Van Vechten, and three other brief reviews

The book’s freshest insight is the conflict White discerns between Diana’s ferocious ambition, her lifelong sense that she was born for great things, and her publicly professed, quite genuine, commitment to serve others. This, at least, is something that never came up in the contemporary press. If only there were more of it and less background material on various Diana obsessives, from the sculptor who planned a 9-foot-tall, 2-ton bust of her to be placed outside the London headquarters of the National AIDS Trust to the founder of the Diana Circle who insists, “She was definitely murdered.” Whatever White thinks, these profiles don’t enrich our understanding of Diana’s significance in the culture.

White closes abruptly, with a visitor to the Spencer family estate, disappointed by the lack of memorabilia, asking, “Is there nothing else Diana? Is that it?” There’s plenty of Diana in “Dianaworld,” but unfortunately, readers expecting an original take on one of the most analyzed women in the world may well have the same reaction.

DIANAWORLD: An Obsession

By Edward White

Norton, 384 pages, $31.99

Wendy Smith is the author of “Real Life Drama: The Group Theatre and America” and a two-time finalist for the National Book Critic Circle’s reviewing citation.

Comment count: