“Why is Milton so poor?”

It’s the question my 12-year-old son has been asking on and off for the past few months. Apparently our town’s budget crisis is even obvious to a sixth grader.

He asks because his teachers have been rationing paper because there’s no money to buy more. He asks because one of his favorite teachers abruptly quit in February, and I wondered if looming school cuts pushed her to find another job — out of fear she might be laid off.

As a parent, you don’t want your kids to worry about money, and for the most part, my kids haven’t had to — until now.

The absurdity of it all is that Milton is not at all poor. Last year the median sale price of a single-family home in Milton was $1 million, and the median household income is nearly $180,000 a year. Yet Milton is facing a double whammy of money woes: Mid-year school budget cuts and the prospect of higher property taxes with residents heading to the polls Tuesday to vote on a $9.5 million tax override aimed at avoiding deep reductions to education and other town services next year.

Some of the school’s fiscal problems have been self-inflicted — a legacy of flawed accounting practices that have now been addressed — but the upshot is that property taxes in Milton no longer cover our town’s expenses, which have been growing because of sky-high inflation and other rising costs.

“Communities that seem in many ways to be affluent, their city or town government may not be correspondingly affluent,” explained Adam Chapdelaine, executive director of the Massachusetts Municipal Association, an advocacy group for the state’s 351 towns and cities.

And so, for the second time in a decade, Milton town officials are asking residents to vote to override Proposition 2½, the 1980 state law that restricts how much a municipality can increase its property tax collection.

Voters in a state-wide ballot initiative approved Prop. 2½ in a bid to rein in out-of-control municipal spending, but decades later the concept has failed to keep up with expenses of modern times. School budgets, in particular, have gotten bigger to accommodate the growing number of students with disabilities that require costly services, from specialized therapies to one-on-one aides. Add in high energy prices and soaring costs of health insurance for town employees, and tax revenue hasn’t kept pace with the bills.

Milton’s hardly the only Boston-area suburb facing this predicament. Other towns from Brookline to Acton have faced similar financial challenges and have had to go to the ballot box in recent years to resolve budget shortfalls.

Mass. communities increasingly seek overrides to tax cap to pay for schools, other services

During the pandemic years, federal money helped Milton and other towns put off raising taxes, but now those funds have run out. About 50 towns in Massachusetts held tax overrides last year, compared to an average of 24 override votes in the four years prior, according to an analysis by Chapdelaine.

He expects this year to be historically high for overrides. So much so that he thinks it’s time policymakers consider whether the current municipal tax structure is sustainable.

”Prop. 2½ is under more strain than it’s ever been,” said Chapdelaine. “It’s likely time for a dialogue around Prop. 2½’s efficacy as we try to maintain city and town services.”

I’m not happy about paying higher taxes, but I’ll be voting yes Tuesday because Milton schools really can’t afford to lose more. This would be the biggest override request in town history. But if it doesn’t pass, the school system that serves about 4,300 students would have to slash school spending by about $6.3 million, or nearly 10 percent of its budget. That could mean a loss of 76 positions, including dozens of teachers and specialists, and cuts to clubs and sports.

Milton town website: Homeowners can calculate override impact on their tax bill

Supporting the override means my own property tax bill is estimated to go up by about $1,250 to about $15,000. That’ll hurt.

But it’s a worthy investment in a town I love and have called home for 15 years. This is what it means to be part of a community. You come together in times of need. Plus, I want to pay it forward. Both of my sons are on the autism spectrum, and when they were in preschool and kindergarten, they benefited from Milton’s specialized educational services — support that helped them become the high-functioning kids they are today.

Mike Baker, a Milton resident who is an instructional aide at Pierce Middle School, will also be voting yes, but it still may not be enough to save his job. He’s low on the seniority list at Milton’s only middle school, and the override plugs future budget gaps, not the current one.

He’s voting yes to ensure that his son, who is a sixth grader at Pierce with my son, will get a good education. Our kids also know each other from playing on the town’s travel basketball team the past three seasons.

“We live in one of the richer towns in the state of Massachusetts and to have to even do a vote at all is kind of disheartening,” said Baker. Still, he calls the override a “necessity.”

Despite Milton’s affluence, it doesn’t have much of a commercial tax base, and that means residential property taxes are high. My tax bill is already close to double the state average of about $7,700. Gulp again. There’s not a lot of new development to help absorb rising costs, either.

Of course, we could fix that part, but as the first municipality where voters rejected a state-mandated zoning plan for more multifamily housing, Milton has become the poster child for anti-development sentiment. Milton remains at odds with the state housing law — even after losing in January a lawsuit filed by Attorney General Andrea Campbell that went all the way to the Supreme Judicial Court.

So will a “yes” vote prevail?

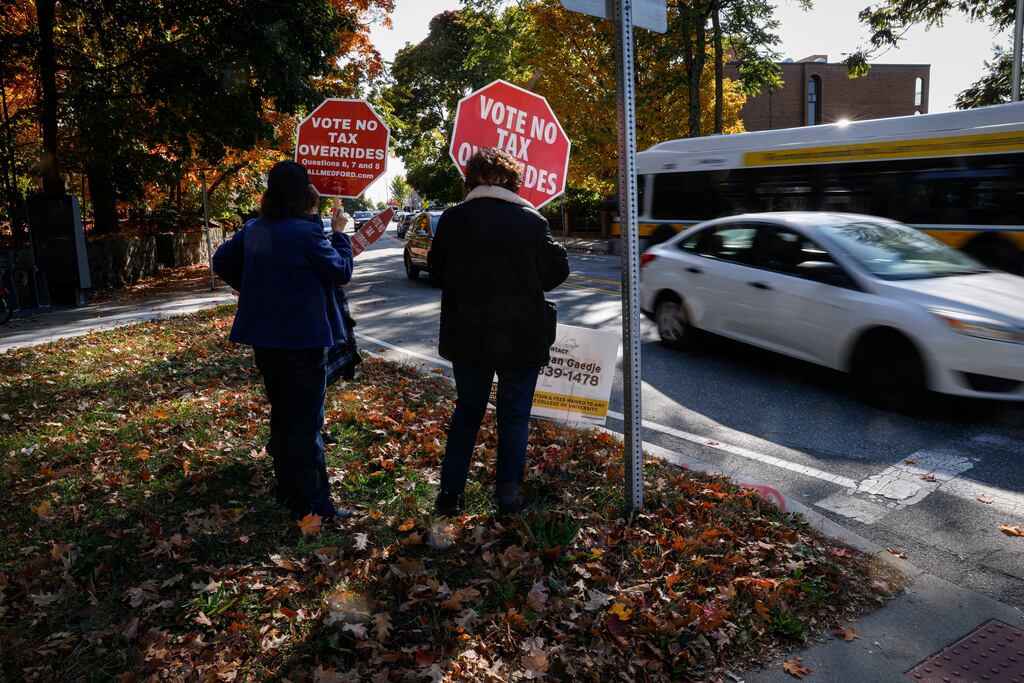

Elizabeth Carroll, chair of the Milton School Committee, said she feels “cautiously optimistic.” One indication: Drive around town, and you only see “Vote Yes! For the Override” lawn signs. Supporters have been out in force, knocking on doors and even hosting an information session at a recent bingo lunch at the senior center.

“We don’t have a visible ‘no’ campaign,” said Carroll. “Other towns you see no signs. That makes me optimistic.”

Let’s hope the signs have it right — and that Milton chooses to invest in its kids and its future.

Brett Phelps/Brett Phelps for The Boston Globe

Comment count: