One of my favorite short stories by Jess Walter is “The Way the World Ends,” a one-crazy-night tale about a frustrated climate scientist named Anna Molson who, when thinking about the stupor so many Americans evince in the face of Earth’s ongoing environmental collapse, “always gets the urge to scream at a whole distracted world.” Walter wrote the story, which concludes his 2022 collection “The Angel of Rome,” early in the first Trump administration as the United States was abandoning its environmental commitments and initiatives, yet he ended it on a hopeful note, with a Southern community grudgingly permitting a Pride parade to march through town.

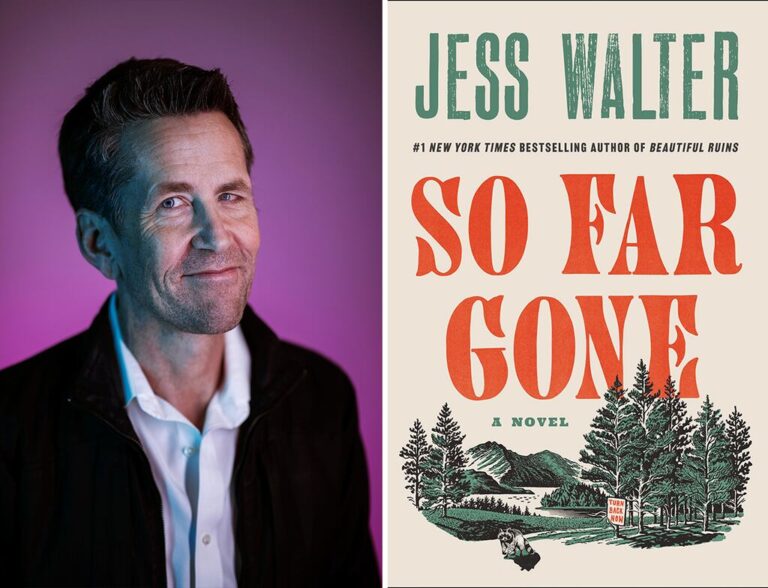

One global pandemic and a few more years of Trump later, and Walter is back, this time with a novel, his eighth, titled “So Far Gone.” The urge to scream has persisted in reclusive former environmental journalist Rhys Kinnick, who doesn’t suppress the desire like Anna did, but any sense of optimism is absent, despite an unconvincing attempt to end on a glimmer of hope. “So Far Gone” is set in May 2024, but its inciting incident occurs on Thanksgiving Day 2016 when, in the wake of “the recently decided dumpster fire of an election,” Kinnick calls Shane, his red-pilled son-in-law, an “idiot” and then punches him. Two months later, having thrown his cellphone out the window while speeding down the highway, Kinnick retreats to his family’s 40-acres northwest of Spokane and settles into seven-plus years of fancying himself a 21st-century Thoreau; reading mostly books written by dead white guys; writing his “Atlas of Wisdom”; and reconciling himself to a world that “was drifting in one direction [while he] was going the other way.”

Working on union blues in ‘The Cold Millions’

Kinnick’s attempt to suck the marrow out of life is interrupted when his grandkids, 13-year-old Leah and 9-year-old Asher, are delivered to his doorstep after their mother, Kinnick’s daughter Bethany, disappears. Kinnick initially doesn’t recognize his progeny, whom he hasn’t seen since a socially distanced visit early in the pandemic, and their awkward reunion is cut short when the kids are snatched by the Army of the Lord militia acting at the behest of Shane, who is Asher’s father and Leah’s stepdad. Adding injury to insult, one of the goons even smacks the 60-something Kinnick with a blackjack. The militia is linked to Shane’s house of worship, the Church of the Blessed Fire, which has a “safe zone” for Pacific Northwest Christians called the Redoubt. Shane and Bethany, who met at a Narcotics Anonymous meeting, were drawn together by their faith, but Blessed Fire is a bridge too far for her, drawing Shane into “nutty Christian nationalism” and proposing that Leah “betroth” the pastor’s 19-year-old son.

Kinnick’s quest to rescue his grandkids and find his daughter is aided by his Indigenous friend Brian, a member of the Spokane and Colville tribes; his former girlfriend Lucy, a foul-mouthed, 106-pound, Asian American newspaper editor; and “Crazy Ass Chuck Littlefield,” an ex-cop turned private investigator who dated Lucy after Kinnick. The action moves from the Washington woods to a militia training facility called the Rampart to an Incan-inspired music festival in Canada. Walter includes edifying asides about climate change, property crime, and the abuses inflicted on Indigenous people, but his comedic touch, which lent levity to his earlier work, is off here.

Jess Walter on trying not to hoard beloved books

The novel has genuinely severe consequences for some characters, but it also makes a lot of excuses for people, presenting some militia members as just misunderstood or misguided, and Kinnick concludes a profanity-laden screed about the 2016 election by saying that Trump voters “weren’t really the problem” because “maybe they were just burned-out and believed that corruption had rotted everything, that one party was as bad as the next; or maybe they really did long for some nonexistent past.” This would be a pleasant read in a vacuum, but in the world that it’s attempting to comment on, it can feel obtuse. I had the urge to scream when Kinnick rhetorically asked “Was this just how people behaved now? Is this what the world had come to?” Yes, it is. We need to accept how far gone we are or this will be the way our world ends.

SO FAR GONE

By Jess Walter

Harper, 272 pages, $30

Cory Oldweiler is a freelance writer.

Comment count: