Single-family neighborhoods are synonymous with the American Dream. Their driveways and grassy yards define the communities of suburban America, including Greater Boston.

But are they also compounding Massachusetts’ deep housing crisis?

A state-appointed commission focused on the state’s worsening housing shortage in fact identified single-family-only zoning — the land-use rules that created suburban single-family neighborhoods — as a primary obstacle blocking the surge of construction Massachusetts desperately needs to address its housing problem.

And so the commission proposes a seemingly profound idea: get rid of single-family zoning — everywhere in Massachusetts.

Instead, state leaders should adopt a new zoning regime that would allow property owners to build small, multifamily homes on virtually any residential lot.

The recommendations in a report from Governor Maura Healey’s Unlocking Housing Production Commission issued Friday would not prohibit the construction of single-family homes. But, if adopted, they would limit local governments from blocking many multi-unit projects on leafy suburban streets.

Such a move would require approval from the state Legislature, and would no doubt meet intense political opposition.

But the commission argued there are no simple, painless adjustments that can meet the scale of the state’s massive shortage of homes. A full-scale rethinking of how homes in the state, both market-rate and affordable, are planned, permitted, financed, built, and maintained is necessary to make meaningful progress.

“The time for incremental change has long passed,” the commission wrote. “Bold, decisive, continued action is essential to ensuring that Massachusetts remains a place where people can afford to live, businesses can thrive, and communities can grow.”

The recommendations — which are suggestions for Healey to consider, not a formal legislative agenda — followed an analysis earlier this month by the Healey administration that found the state needs to build 222,000 homes by 2035 to fill a yawning supply gap that is driving up the cost of housing for everyday people. At the rate new housing is being added currently, the state will fall well short of that goal.

And preempting single-family zoning is only one of the potentially foundational changes laid out by the housing commission, which is chaired by Healey’s housing secretary. The commission also called for the elimination of minimum parking requirements for new housing projects, which could free up valuable land for additional units and reduce the cost of building, and it urged the state to consider withholding state aid from communities that don’t comply.

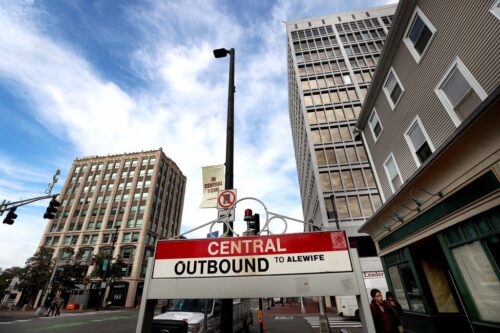

The recommendations come as the state has been at odds with local governments over housing. Some communities in Greater Boston have balked at measures intended to remove roadblocks to construction near transit stations, and some of the commission’s recommendations could go further in overriding local authority.

In a statement responding to the commission’s recommendations, the Massachusetts Municipal Association said it “would have significant concerns about many of the proposals.”

A number of other states, including Vermont and Maine, have passed similar reforms, though they have been controversial. The idea, advocates say, is to add modest density in the form of duplexes, triple-deckers, and fourplexes — the sort of housing many towns used to build before the buildings were banned in most places — in single-family neighborhoods without dramatically disrupting the character of a community.

Cambridge enacted a similar policy last week, allowing buildings up to six stories citywide.

The proposal would not preclude the construction of single-family homes, but rather it would allow denser homes to be built in addition to single-families in neighborhoods statewide.

It also proposed tying more municipal funding — like school and highway funds — to state housing goals, so that “communities will have stronger incentives to adopt pro-housing initiatives.”

And the commission suggested eliminating minimum lot size requirements for residential land. More than half of the cities and towns in Eastern Massachusetts mandate that some lots for single-family homes be at least 1 acre. Some require a baseline of 2 acres, 1½ times the size of the playing field at Gillette Stadium, per house.

Some land-use experts contend such large lots are a waste of land in a state where it is an expensive commodity, and those rules are a relic of an era when zoning was used as a tool of exclusion. Getting rid of those lot-size requirements would make it easier to build smaller, more affordable homes, and make better use of the state’s land, the commission said.

“By requiring excessive amounts of land per home, these regulations inflate housing costs, limit the availability of buildable land, and reduce housing diversity,” the committee wrote.

Another of the reforms outlined by the commission is the end of minimum parking requirements for new development statewide.

Parking minimums are commonplace in cities and towns across the state. They mandate new housing developments are built with a certain ratio of off-street parking spaces designated for residents of the development. But those parking spaces are expensive: In some communities, it can cost developers more than $100,000 to build a single space, and those costs are transferred directly on to tenants in the form of higher rents.

What’s more, many parking minimums require developers to build more spaces than residents use. A 2023 study by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council found that some 40 percent of parking spaces in six communities surrounding Boston were empty during peak hours. Instead of building excess parking, the report said, that land could be used for housing.

Eliminating parking minimums would not mean banning off-street parking. It also would not mean that developers would stop building it, the commission said. Rather, they would build parking to market demand. Cambridge and Somerville have both eliminated parking minimums in recent years.

Of course, making the commission’s recommendations a reality is another question. Changes to housing policy in Massachusetts are always controversial, particularly when they involve the state influencing local land-use decisions.

Virtually every reform the commission proposed will likely have powerful adversaries, because those proposals in many cases suggest undoing rules that have shaped what housing is built here, and how, for decades.

“Any of these suggestions is going to require some soul-searching if we want to implement them,” said Jesse Kanson-Benanav, executive director of the housing group Abundant Housing Massachusetts, who served on the commission. “It’s going to be a hard conversation, but it’s a conversation we must have. Because what we’re doing right now is not enough.”

The commission’s final proposal was more than 100 pages long. Here’s what else it suggested:

- Bolster financing programs for water and sewer infrastructure expansion, with the eventual goal of connecting more municipalities to the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority and other regional water and wastewater systems.

- Dedicate additional resources to studying modular, or factory-built, housing, with the goal of opening large modular factories in Massachusetts to build units for local development projects.

- Streamline approvals for Chapter 40B housing projects, which lets developers bypass local zoning rules in communities that do not have a certain amount of affordable housing.

- Create an Office of State Planning to coordinate long-term land-use policy goals, and closely track municipal development data to measure progress.

- Require municipalities to set standards that adhere to, but don’t exceed, the state Department of Environmental Protection’s wetlands and wastewater requirements, a measure intended to remove onerous rules that can block new construction.

- Allow residential buildings of up to 24 units and six stories to only have a single staircase, as opposed to two, to help reduce the cost of small and mid-size development.

In dramatic overhaul, Cambridge becomes one of the first cities in Mass. to eliminate single-family zoning222,000 new homes must be built over the next decade to fix housing shortage, state saysAs Kraft spars with Wu, one thing is for certain: The Boston mayoral race will be about housingThe latest consequence for rejecting a state housing law: Firefighter equipment grants

Comment count: