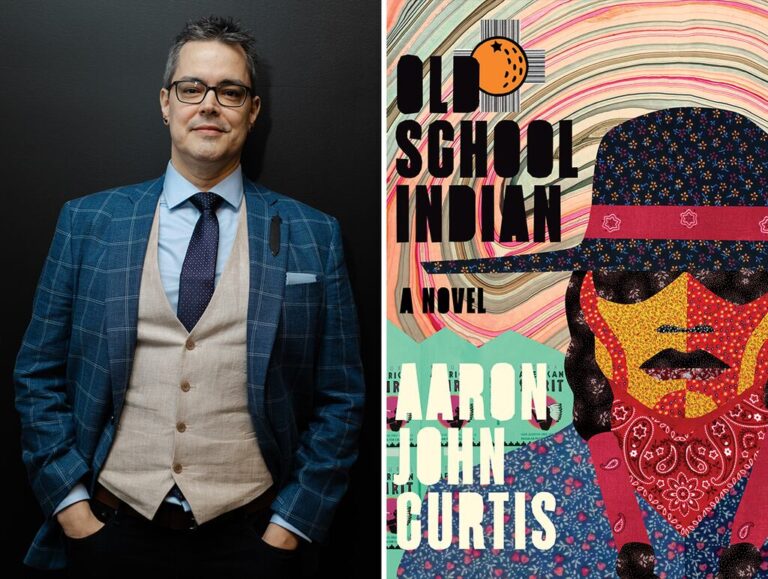

“Old School Indian,” Aaron John Curtis’s wonderfully voicey debut novel, which he describes in an afterword as “full autofiction,” opens with a note from Dominick Deer Woods, who turns out to be the alter ego of the protagonist, Abe Jacobs. Before we begin, Dominick wants us to learn one word in Mohawk: the word for grandparent, Tóta. “It’ll bring us closer together, I promise.” After thoroughly explaining the pronunciation of those two syllables, he warns us that he’s going to use the term “Indian” interchangeably with Native, Mohawk, Kanyen’kehà:ka, First Nations, NDN, and Indigenous.

“If you find ‘Indian’ jarring the first time you come across it, please keep going. I promise we’ll gut that particular fish later.” And he does. Dominick Deer Woods is a bit of a wiseass, but he’s a fine and reliable storyteller, a committed tour guide, and a gifted poet. You’re going to end up liking him.

Then he officially opens the curtains on Abe Jacobs, who is Kanyen’kehà:ka from Ahkwesahsne, in other words, a Mohawk Indian from the St. Regis tribe on the New York State/Canadian border. Forty-three-year-old Abe has been diagnosed with a disease called Systemic Necrotizing Periarteritis (SNiP) — rare, usually fatal, and a fictional stand-in for a real disease from which the author is in remission called polyarteritis nodosa. Indeed, the details of the painful lesions it causes seem too nasty and specific to make up.

Abe has been living in Miami for the past 20-some years, and his doctors down there are quite a pair: “Dermatologist Unger, a zaftig Teutonic femme fatale from some old black-and-white movie, and Rheumatologist Weisberg, who is small, loud, and whippet-thin, live in the same high-rise on Key Biscayne. They’ve bonded over Abe’s case. They’ll get together for dinner, then call Abe around nine, ten o’clock at night to pepper him with questions about his symptoms — Unger on the phone, sounding like she was a few glasses of wine deep, Weisberg yelling in the background.”

Since Unger and Weisberg aren’t making much progress with his condition, Abe has come home to The Rez to present himself at the trailer of his great uncle Budge Billings, whose healing powers he’s not sure he believes in, but at this point — why not?

Along with the story of Abe’s treatment by Budge, set in 2016, Dominick has several other matters to fill us in on. Abe’s great love affair with Alex, a Florida girl he met in college at Syracuse in 1992 is one of them, the basis of some of the book’s most beautiful passages, as well as a fair amount of intense and graphic sex. (Alex is a natural born polyamorist, and Abe follows her lead as best he can.)

During a scene at Tóta’s deathbed, we learn that there’s no word for “love” in Mohawk. This is not necessarily a bad thing, our narrator explains: “You’d have to express those feelings your own way, different for each person — maybe even differently every time — to show your family, friends, and partners how special they are. Time without you scatters my mind over the ground. The blood that flows belongs to you. Speaking with you is cold water on a summer day. But English gave us “love,” so nowadays people rarely make the effort.”

Dominick/Abe, however, will indeed make the effort, and buried in this novel is one of the most beautiful love poems this reader has encountered in some time, presented by Abe to Alex at her birthday party. It’s sandwiched in between some excellent food writing and a description of a bar fight — because that Dominick Deer Woods, he’s got a big bag of tricks and he’s a show-off for sure. He can’t just make up one fake name for the author’s real disease — Systemic Necrotizing Periarteritis — he also has Uncle Budge refer to it as “Systemic Necco Wafer Perrier” and then points out why jokes like that are important: “Abe admires his uncle’s dedication to never calling his disorder by its rightful name. Trying to get me to be less afraid of it, Abe thinks.”

Morgan Talty on a shift in literary representation of Indigenous authors

Which is why the sly humor never stops, even in the most painful passages. Reflecting on his childhood in an early conversation with Alex, Abe recalls a suicide attempt he made at the age of 7. When Alex, dumbfounded, asks why, he explains that his dad was an alcoholic, and in alcoholic families, the kids take on certain roles. His older brother, Adam, was the Hero, his older sister, Sis, was the Scapegoat, and he was the third born, the Lost Child, and they kill themselves. “I’ll tell you, you haven’t lived until you’ve seen the worst truth of your life typed out in a little pamphlet.”

Oof.

This novel is sure to be compared to the work of great Native writers like Tommy Orange, Morgan Talty, and Louise Erdrich, and I also thought of Ayad Akhtar’s terrific autofictional novel “Homeland Elegies.” If you pick it up, you won’t put it down. Dominick Deer Woods makes sure of that.

OLD SCHOOL INDIAN

By Aaron John Curtis

Zando, 352 pages, $28

Marion Winik hosts the NPR podcast “The Weekly Reader.” She is the author of “The Big Book of the Dead.”

Comment count: