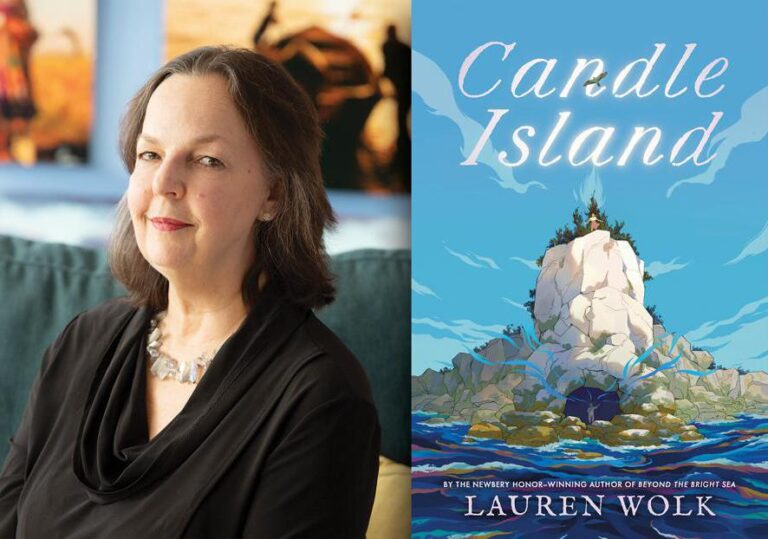

There’s no major external drama in Lauren Wolk’s new middle-grade release, and therein lies its magic.

In Gen Alpha’s speed-scrolling no-attention-span-required world, middle-grade novels tend to blare neon lights — battles, dragons, wizards, super powers — to flag down tween-attention. In contrast, Wolk’s “Candle Island’’ (April 22) is a soft hushed glow.

Set on a spit of island off Maine’s coast, it centers on three New England kids. Our narrator Lucretia — a 12-year-old painter, synesthete, and animal lover — leaves Vermont with her mom and horse for tiny Candle Island.

Lucretia befriends Bastian — who secretly sings opera and wants to learn Italian — and his cousin Murdock, who lost both her parents and secretly writes (impressive) poetry.

Its plot-pace a gentle cantor, a main story line involves Lucretia caring for a baby osprey and quietly grieving the (off-screen) death of her father. High dramas include sharing each other’s art or poetry without consent, and dealing with the snobbery and pranks of the summer resident kids.

The island feels tinged in sepia-toned nostalgia — no computers, no cellphones. There’s plenty of pie-baking, and grilled cheese sandwiches with apples. The novel never spells out what year it is, so I found myself searching for clues: When mom ends a phone call, Lucretia notes mom “put down the receiver’’ — obsolete vernacular for 12-year-olds in the last decade.

’’I think it’s probably around 1967, but I can’t be completely certain,’’ Wolk, 65, tells me with a laugh in a phone interview from her Centerville home. “I wanted it to feel a little timeless.’’

Toward the end of the book, it feels like her thesis when one adult comments: “Are all the kids on this island creative geniuses?’’ and Lucretia replies: “Yes. All the kids in the world are…’’

And if Lucretia and her pals seem older than 12? Wolk is aware.

“Sometimes people say, ‘Your characters are way too mature. That’s not realistic.’ Well, that’s balderdash. I spend a lot of time with kids. I was a kid. There are a lot of very wise and intellectually curious kids,’’ she tells me. “Those kids inspire me, and they end up in my books. And if they’re not typical? Well, good.’’

Wolk grew up largely in Providence, and summered in Cotuit. After graduating from Brown in 1981, she moved around, eventually landing in Centerville. Her other middle grade novels include “Wolf Hollow’’ (2016), which won the Newbery Honor, and “Beyond the Bright Sea’’ (2017), which earned the Scott O’Dell Award for Historical Fiction.

I called Wolk ahead of two Cape events — April 30 at the Sandwich Public Library and May 31 at the Cotuit Library — to talk Maine islands, Nantucket Quakers, writing by the seat of your pants, the loneliness of childhood, and more.

Q. So what sparked “Candle Island’’?

A. I’m involved with Island Readers and Writers, a nonprofit in Maine that brings authors and illustrators to tiny schools, often on their islands, where there might be 12 or 15 kids from K-8. It’s an incredible organization. I’ve spent a fair bit of time on these little islands, listening to kids talk about their lives. I wanted to write a book with a very strong setting, on a shore. Spending time in these schools really tipped the balance.

Q. Is Candle Island inspired by a particular island?

A. Probably Vinalhaven and North Haven together. It was great spending time with kids, teachers, and librarians there. I got a glimpse into how they live.

Q. Lucretia tells us she’s named after Nantucket Quaker/feminist activist Lucretia Mott. Why Lucretia Mott?

A. [laughs] This is like true confessions: I do very little research even though I write historical fiction, because I find research steers the story too much. I just research when I have a question, and often, as I’m researching this or that, I uncover fascinating things that influence the flavor of the book.

I’m a pantser — I don’t write with a map. I thought of [the name] Lucretia and looked for historical people named Lucretia. I’d heard of Lucretia Mott, but I didn’t know much about her. I thought it was a lovely association. So many things in my books come from stumbling over information that lights me up.

Q. You said you think this takes place in 1967.

A. I can’t be completely certain … but it’s interesting. When you go out to those little islands, it’s like a time-machine. They have computers, cellphones — but it’s old-world, too. Strong families where, generation after generation after generation, they fish, lobster. You feel this sense of timelessness. I wanted to capture that.

Q. There is plenty of old-school charm here. Like Lucretia biking to the library to look up a quote.

A. Exactly. I always put my own childhood into things. Growing up on the Cape in the summertime, we went everywhere on our bikes.

Q. Bastian secretly sings opera by the cove. What inspired that?

A. I don’t know. [laughs] When I say I’m a pantser, I mean it. I shock myself all the time. I’m like: I have a first line. I have a setting. I have one character. Let’s see what happens. Oh! There’s a bluff. Let’s take Lucretia to the edge. The wind is blowing. What’s that she’s hearing? I’m not an opera buff, but all of a sudden, Lucretia and I are hearing this singing. … I have faith in my characters to lead me somewhere interesting.

Q. You say you’re a pantser — but do you have any idea of plot? Did you know she was a painter?

A. I spend a lot of time in my head before I start writing, just watching my character living. She’ll do something that reveals who she is. In this case, she quickly revealed herself as somebody who loves to paint, and loves color. She’s got — I don’t call it synesthesia, but the way she interacts with the world is influenced by color. I knew she’d encounter other kids who were also secretive about their creativity.

Q. You get into class differences, by having the summer residents versus the year-round kids.

A. I think it was on my mind because of how the Cape works. When I was a kid, I was one of the summer people. We weren’t rich summer people — I worked as a waitress. The way people treated me was eye-opening. So even though I’m a very lucky, privileged person compared to most, I am very aware of class differences and I find them upsetting.

Q. Did you always want to be a middle-grade writer?

A. It never occurred to me. In fact, I wrote “Wolf Hollow’’ for adults. My agent said, “Oh no, this is a coming-of age story. This is middle grade.’’ I thought, “OK, I can see that.’’ I really don’t write for middle grades. I just write books that happen to have 12-year-old protagonists.

Q. What were you like as a kid?

A. I was a weird kid. I’m still a weird kid. An introvert desperately trying to be an extrovert. The things I was most shy about, I now love best about myself. I’m always telling kids: “The stuff you’re hiding, that’s what you’ll want to highlight later.’’ I was a highly sensitive kid, very attuned to everything around me, which can be painful. But it’s a great way to feed your creative soul.

Q. What were you trying to hide that you now highlight?

A. Pretty much the way I see the world. It’s hard. You’re there with your friends, and all they’re talking about is boys, all they want to do is go out. I would’ve been much happier just being alone.

Some kids are loners. It’s hard to be a kid and be alone. You’re supposed to be figuring out the world. The best way to do that, in a lot of ways, is with companions. But I was and still am— boy, there’s like a therapy session — most comfortable alone.

Q. I feel that. For kids like us, there’s something really relatable in this book.

A. Yes. And it doesn’t mean she doesn’t want friends — it just means she knows who she is and what she wants, and it’s hard to find those things when you’re with other people.

Q. What do you want kids to get out of this book?

A. That they should be their own authentic selves. Stand up for what they believe in. Express themselves in any way that feels right for them. They should be proud of who they are.

Interview was edited and condensed.