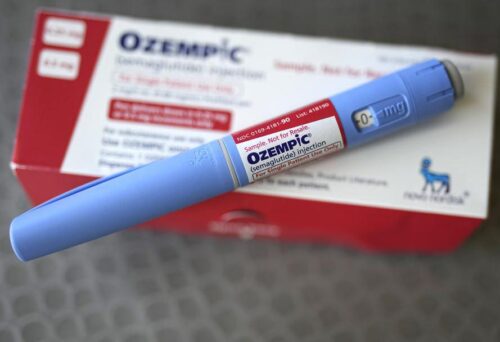

A daily pill may be as effective in lowering blood sugar and aiding weight loss in people with Type 2 diabetes as the popular injectable drugs Mounjaro and Ozempic, according to results of a clinical trial announced by Eli Lilly on Thursday morning.

The drug, orforglipron, is a GLP-1, a class of drugs that have become blockbusters because of their weight-loss effects. But GLP-1s are expensive, must be kept refrigerated, and must be injected. A pill that produces similar results has the potential to become far more widely used, though it is also expected to be expensive.

“In the coming decades, more than 700 million people around the world will have Type 2 diabetes, and over a billion will have obesity,’’ said Dr. Daniel Skovronsky, Lilly’s chief scientific officer. “Injections cannot be the solution for billions of people around the world.’’

Lilly said it would seek approval from the Food and Drug Administration later this year to market orforglipron for obesity and early in 2026 for diabetes.

Industry analysts expect the drug to win approval sometime next year. Eli Lilly is not expected to announce a price for the drug until after it wins approval.

The company announced a summary of its results Thursday in a news release, as drug companies are required to do immediately after they receive study results that could affect their stock price.

The company said it would present the detailed results at a meeting of diabetes researchers in June and will publish them in a peer-reviewed journal.

Lilly did not release the underlying data from its trial and the results it disclosed had not been examined by outside experts.

The clinical trial involved 559 people with Type 2 diabetes who took the new pill or a placebo for 40 weeks. In patients who took orforglipron, blood sugar levels fell 1.3 to 1.6 percent, as measured by an A1C test, about the same amount as patients taking Ozempic and Mounjaro in unrelated trials. For 65 percent of people taking the new pill, blood sugar levels dropped into the normal range.

Patients on the new pill also lost weight — up to 16 pounds without reaching a plateau at the study’s end. Their weight loss was similar to that achieved in 40 weeks with Ozempic, but slightly less than with Mounjaro in unrelated trials.

Side effects were the same as those with the injectable obesity drugs — diarrhea, indigestion, constipation, nausea, and vomiting.

It is possible that when the drug is used in much larger numbers of patients, the benefits could be smaller and the side effects worse.

Eli Lilly is at the front of a pack of companies racing to develop GLP-1 pills, and there are major concerns that such pills could cause harsh side effects that discourage patients from taking them.

Earlier this week, Pfizer said it had decided to stop developing a GLP-1 pill after a trial participant experienced a “potential drug-induced liver injury.’’

Eli Lilly’s stock surged on the encouraging data. It was up 14 percent when the market opened Thursday, adding $100 billion to the company’s market value.

This was the first of seven large clinical trials of orforglipron to report results. Some of the others are testing the drug for weight loss in people without diabetes. Results in patients with obesity are expected later this year.

If the drug is approved for obesity and diabetes, Skovronsky said, the company is confident it will have sufficient amounts of the pills to meet demand. He said he had learned the results of the diabetes study Tuesday morning, but without even knowing them, the company had been preparing supplies.

Some 12 percent of American adults say they have taken a GLP-1. About 40 percent of Americans are obese, and more than 10 percent have diabetes, most of whom have Type 2, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a way, the very existence of orforglipron is a triumph of modern chemistry. The injectable GLP-1 drugs are peptides — small fragments of proteins. (GLP stands for glucagon-like peptide.) Peptides are digested by the stomach. So, in order to make an oral GLP-1, chemists had to find a way to make a nonpeptide that acts exactly like a peptide. Researchers at Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., a Japanese company, figured out a way, licensing their drug to Lilly in 2018.

The solution was to find a small molecule — thousandths of the size of a peptide — that sinks into a tiny pocket in the protein that is the target for GLP-1s. When it sinks into the pocket, the protein changes shape, just as it does when a GLP-1 binds to the whole protein.

Finding that small molecule, Skovronsky said, was “the holy grail.’’

The result — a pill that can be taken at any time of day, with or without food — is almost unheard-of in the world of peptide drugs.

Insulin, probably the most common peptide drug, has been around for more than 50 years. It is still only an injectable, despite intense efforts by scientists to make an insulin pill. So is human growth hormone and drugs used to treat a wide variety of diseases, including arthritis and cancer.

Novo Nordisk has a GLP-1 pill, Rybelsus, but it contains the GLP-1 peptide, so it must be taken in large doses and is not as effective as the injectables because most of it is digested.

But for patients with diabetes and those struggling with obesity, a pill that can replace an injection can be transformative, for several reasons.

One is that it can make treatments attractive to those who cannot bear the idea of injecting themselves.

Dr. C. Ronald Kahn, a professor of medicine at Harvard University and chief academic officer at Harvard’s Joslin Diabetes Center, said he had many patients who were reluctant to inject themselves with Ozempic or Mounjaro.

A pill, he said, “would definitely be preferred by most people.’’

Dr. Sean Wharton, director of the Wharton Medical Clinic in Burlington, Ontario, has a broader hope.

Wharton, who enrolled patients in Lilly’s study of orforglipron for obesity, said a pill could potentially bring GLP-1 treatment to underserved populations throughout the world.

“It can be easily made in a factory and shipped everywhere,’’ he said.

It should cost much less to make than peptides and does not require packaging in special injection pens. It does not have to be kept refrigerated.

With orforglipron, “we have a chance of a medicine being given to millions and millions of people,’’ Wharton said.

But that depends on Eli Lilly and how it chooses to price and distribute its drug.

“That’s why I emphasize the word ‘chance,’’’ Wharton said.