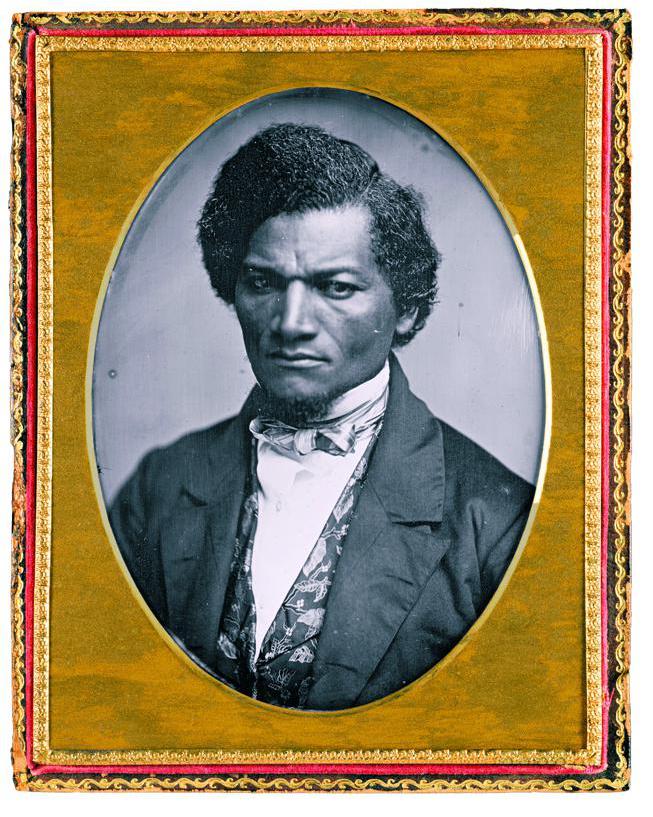

I’m currently leading my freshmen students through a weeks-long seminar on “The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass,’’ a searingly brutal account of the slavery Douglass endured and the freedom he chased. Our conversations have been candid. Douglass explores insightfully the psychological effects of slavery on slaves and slaveholders alike, and offers compelling explanations of how the institution weakened and almost extinguished the American moral imagination.

Douglass has been taught in American classrooms for decades. He’s a towering literary figure, a public philosopher with few equals, and an unmatched orator. He’s exactly the kind of important figure that ought to be a staple in history, literature, and philosophy classes.

But as my students and I have been studying his life and writings, I’ve wondered whether some Americans and political leaders might accuse me of “doing DEI.’’

On Jan. 20, President Trump made good on a campaign promise when he issued an executive order to “coordinate the termination of all discriminatory programs, including illegal DEI and ‘diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility’ (DEIA) mandates, policies, programs, preferences, and activities in the Federal Government, under whatever name they appear.’’

As a judge in Baltimore later pointed out in a ruling that largely blocked the order, this has chilling implications for education. “If an elementary school receives Department of Education funding for technology access, and a teacher uses a computer to teach the history of Jim Crow laws,’’ he speculated, “does that risk the grant being deemed ‘equity-related’ and the school being stripped of funding?’’

As if to try to remove any doubt, Trump’s Department of Education argued last month that it does have the right to prohibit the teaching of some ideas about race. A few days later, it launched the website EndDEI.gov, a public portal where concerned parents and other members of the community can submit complaints that a teacher dared to run afoul of Trump’s anti-DEI initiatives.

The Baltimore judge essentially asked the question that’s been on my mind ever since Trump promised to “end DEI’’: Can I still teach subjects the way I believe they ought to be taught? What if, at my Catholic school, I call attention to the passages in Douglass’s text that acknowledge Southern Christian slaveholders’ biblical arguments in favor of slavery? Is this, because it casts some white American Christians in a bad light, “doing diversity’’?

Earlier this semester, I taught Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice,’’ which tackles antisemitism. Portia, the ingenue to whom Shakespeare gives the unmatched “The quality of mercy is not strained’’ speech, nevertheless comes across as racist. Can I point this out to students? What if I suggest that Shylock’s “Hath not a Jew eyes?’’ speech is intended to challenge antisemitic attitudes in Shakespeare’s day?

What about when I showed students the film of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 2014 production, in which Shylock was played by an Israeli Arab? Should that be seen as a kind of DEI commentary on current events?

This same production, paying particular attention to a not-so-subtle subtext that virtually all Shakespeare scholars acknowledge exists between Antonio and Bassanio, saw the two men share a kiss. Because I, a gay man, showed this film to my students, was I up to something? Should this be seen as my agenda?

There are obviously some valid criticisms to level at some institutional DEI initiatives, just as there are valid criticisms to level at other aspects of university administrations. But the blanket condemnation seems vacuous. Because what seems to count as “diversity’’ to its critics is any instance of a teacher asking a student “Have you thought about it this other way?’’

If teachers are now being discouraged from bringing such very basic questions into our classrooms, then higher education is just not possible.

The EndDEI.gov site and Trump’s other attacks might call to mind additional instances of creeping government interference in education. As plenty of historians have shown, there are eerie parallels between McCarthyism and current antidiversity movements spearheaded by MAGA politicians.

“Trumpism is the New McCarthyism,’’ wrote Ellen Schrecker, who has published several books on McCarthyism, back in 2018. In fact, she argues that what’s happening today is actually much worse than what happened in the 1940s and ’50s. That’s because while the red scare certainly had a chilling effect on campuses, “it did not interfere with such matters as curriculum or classroom teaching,’’ says Schrecker.

According to some estimates, about 600 teachers at all levels of education lost jobs during that era. But the bigger losses came from teachers’ self-censorship. The government’s targeting of individuals with connections to “communism’’ sent a clear message to all teachers: Watch what you say in the classroom.

I agree with Schrecker’s analysis. Republicans who are passing laws to police classroom activity have gone beyond the tactics of McCarthyism. You can easily connect the dots from Representative Elise Stefanik’s war against “woke education’’ to Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s “Don’t Say Gay’’ bill to Trump’s incursions on what many teachers, myself included, believe to be the foundation of American democratic education.

Let’s hope that judicial and public opinion continues to turn against Trump’s dictates. They are both narrowly contrived and overly broad. Narrow because they fixate on individual words like “equity’’ and “accessibility.’’ Broad because they might be leveled against almost anything a teacher might teach.

Think, for instance, about the kinds of diversity that MAGA might like.

Next month, my classes will start reading “The Grapes of Wrath,’’ which tells the story of a poor white family fleeing the devastation of the Oklahoma Dust Bowl. Most of my students do not come from low-income backgrounds. To them, poor, uneducated white people would likely count as “diversity.’’ Am I, then, not to encourage my students to read these characters compassionately and with an eye toward empathizing with their hardships? What about encouraging my students to draw connections between the Joads’ day and our own by noting that John Steinbeck understood that many poor white people feel betrayed by their country and sometimes express that hurt in xenophobic ways?

This is why, even if I were told I was not allowed to use words like “diversity’’ or “race’’ in the classroom, nothing about my teaching would change. Like many professors, I teach students to read against the grain, to challenge consensus readings, to offer creative interpretations of texts in ways that help shed light on our current situation. Higher education exists to invite students both to learn and to question the normative traditions they inherit.

The only other option is to spoon-feed students agreed-upon narratives and to instruct them never to challenge what they learn. Ironically, this would be indoctrination — the very bogeyman the MAGA crowd seems worried about.

Brandon Ambrosino, a theologian and ethicist, is a visiting assistant teaching professor at Villanova University.