PROVIDENCE — Oysters were plentiful in Rhode Island waters in the 1700s, but they were considered food for the poor at the time. So it was unusual for them to be served on expensive pewter platters along with glass cups of ale to the elites of Providence, as well as to ship captains and wealthy merchants who were coming into port.

It was even more unusual for the establishment serving them to be owned and operated by a former slave.

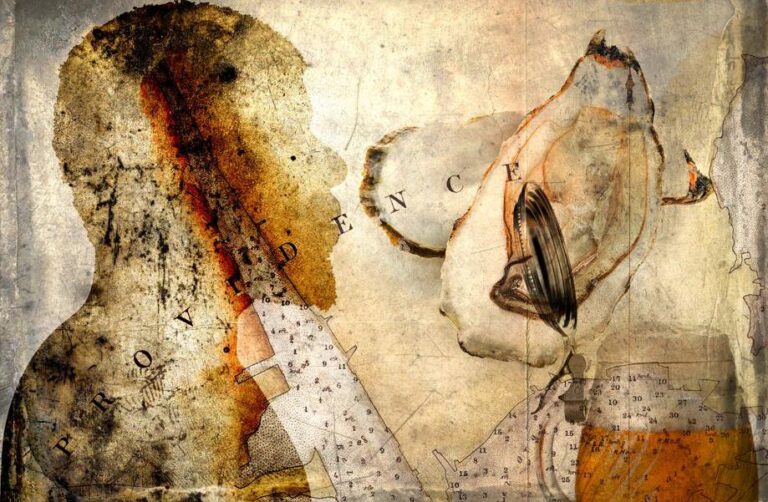

Emmanuel “Manno’’ Bernoon had been enslaved by a prominent merchant from France but, after he was emancipated in 1736, he and his wife opened one of the first restaurants in Rhode Island.

The establishment was located on Town Street, which is now South Main Street, near the site of the old Custom House where Brown University and the Rhode Island School of Design stand today. The business’s name — if it even had one — has been lost in history, much like the story of Bernoon and his oyster house.

“Oysters were sloppy and dirty. And they were cheap,’’ said Robb Dimmick, the co-founder and program director of Stages of Freedom, a Providence-based nonprofit focused on Black Rhode Island life and culture. Oyster houses “were oftentimes cellars and were not glamorous places. And a woman would never go and enter an oyster house.’’

But oysters play a critical culinary role in Black history in America — as much as the ham bones and hominy grits that enslaved people cooked in the South, according to the National Museum of African American History & Culture. On the East Coast, Black vendors would peddle oysters on city streets. They served them raw, fried, or stewed. Black men would often work on schooners as hired crew, operators, and captains, and would gather oysters along the shore.

During the 19th century, long after Bernoon’s restaurant opened, oysters were still associated with working class bars and brothels. And then in 1825 Thomas Downing, an abolitionist and the son of slaves, opened an oyster bar near Wall Street in New York City. The decor was much more impressive than the cellars where most oyster bars were located at that time. He hung curtains in the windows, and a crystal chandelier was suspended over the dining room. Downing’s vision transformed and elevated the reputation of oysters, helping to create massive demand for shellfish throughout the 19th century.

Later dubbed the Black oyster king of New York, Downing was a fine-dining pioneer, who served elite businessmen and rubbed shoulders with wealthy aristocrats. He also created a path to freedom through the oyster industry for those who were still enslaved.

Today, oysters can be found at scores of restaurants across New England. Served mostly raw on a half shell, they can cost anywhere between $1 to $6 each, depending on the type and the season. Over the last decade, Rhode Island’s booming oyster aquaculture industry has been one of the state’s fastest-growing sectors. Aquaculture farmers in Rhode Island sold more than $8 million of oysters in 2023 alone, according to the Coastal Resources Management Council. Across the country, oyster sales reached $327 million in 2023, according to the 2023 Census of Aquaculture, which was released by the US Department of Agriculture in December.

But Downing’s success in New York — and American’s love for oysters — was built upon Bernoon’s efforts in Providence.

When Bernoon opened his restaurant on Town Street, most families cooked at home and dining out was a rarity. But Bernoon’s oyster bar was located nearly at the mouth of Narragansett Bay, so people coming into port had to walk by his oyster house. That attracted business immediately, from sea captains, sailors, merchants, and the residents of the 15 houses along Town Street.

“We know for a fact that Bernoon was serving the elites of Rhode Island and those who came into the port,’’ said Dimmick. “As an emancipated slave, Bernoon satisfied the cravings [of] a thirsty generation and softened the heart of the softening town by way of a gratified and contented stomach.’’

Bernoon took humble oysters and served them on tables set with glass cups and expensive pewter plates — status symbols for the upper and middle classes at the time. Historical records show he had nearly two dozen drinking glasses, four jugs, and 28 glass bottles as well as pewter bowls, plates, and spoons. While more affordable than silver, pewter was still fairly expensive: A single dish cost about as much as a skilled craftsman earned in a day.

Serving oysters on pewter may have been Bernoon’s attempt to elevate them, noted Ray Rickman, Stages of Freedom co-founder and executive director.

“We forget how much food was eaten on wood,“ said Rickman.

Bernoon’s restaurant brought him success. When he died in 1769, he had amassed a house and personal estate valued at 539 pounds — the equivalent of about $175,000 today. He left the estate, 10 shillings, and pieces of china to his wife, according to his will, which is in the city’s archive.

His establishment was “successfully competing with the eating places run by white men,’’ wrote Irving H. Bartlett, an American historian, in his book “From Slave to Citizen: the Story of the Negro in Rhode Island.’’

Bernoon was laid to rest in the North Burial Ground in Providence. His gravestone is in rough shape, and his name is spelled incorrectly as “Amanuel Bernew.’’

Some historians, such as Rickman, also believe Bernoon’s establishment was the first oyster bar in the country.

“There’s nothing else recorded,’’ said Rickman. “So we have to go off of what we know.

Alexa Gagosz can be reached at alexa.gagosz@globe.com. Follow her @alexagagosz and on Instagram @AlexaGagosz.